What is a UCITS ETF? Comparison with US ETFs (2026 guide)

A UCITS ETF is simply an exchange-traded fund that follows a very specific set of EU rules designed for retail investors, people like you and us.

But that small word “UCITS” hides a lot of regulation, and it also explains why European investors often can’t buy the cheaper US-domiciled versions of the same ETFs.

In this article, we will explain everything you need to know about UCITS ETFs.

In a nutshell:

- UCITS ETF = Europe-friendly ETF. It is designed for EU retail investors, must follow strict EU rules (diversification, custody, disclosure, liquidity), can be sold across all EU countries, and is usually domiciled in Ireland or Luxembourg.

- US ETF = America-friendly ETF. It is designed for the US market. Follows US SEC rules, is often cheaper due to scale & US tax structure, and is not allowed to be sold to EU retail unless it has a PRIIPs KID (rare).

So, a UCITS ETF is best for European investors (because it’s the only one your broker is allowed to provide you).

On the other hand, US ETFs are best for American investors (because of tax efficiency and lower cost).

What does “UCITS ETF” actually mean?

UCITS stands for Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities. It’s the main EU framework for retail investment funds.

In summary, a UCITS ETF is an ETF that follows the EU’s UCITS rules.

A UCITS ETF is an ETF that:

- is domiciled in an EU/EEA country (commonly Ireland or Luxembourg),

- complies with the UCITS Directive 2009/65/EC (as amended by UCITS V, Directive 2014/91/EU), and

- can therefore be marketed to retail investors across the EU using a single “passport”.

The UCITS rules set out:

- Diversification rules: no more than 10% of the fund in a single issuer and the famous 5/10/40 rule (no more than 40% of assets in positions above 5%).

- Eligible assets: mainly listed securities and certain derivatives that meet strict criteria.

- Risk-management and liquidity rules: limits on leverage, daily valuation, and liquidity management.

- Depositary & safekeeping: an independent depositary must hold the fund’s assets and is liable for loss in many circumstances.

- Investor information: UCITS funds must provide a short, standardised information document (historically the “KIID”, now usually a PRIIPs “KID”) and a detailed prospectus.

The European Commission itself describes UCITS as one of the EU’s “success stories” in retail investor protection and cross-border fund distribution.

Due to these UCITS rules, you won’t find Bitcoin ETFs, for instance (since they don’t comply with diversification rules).

How to verify if an ETF is UCITS? Example

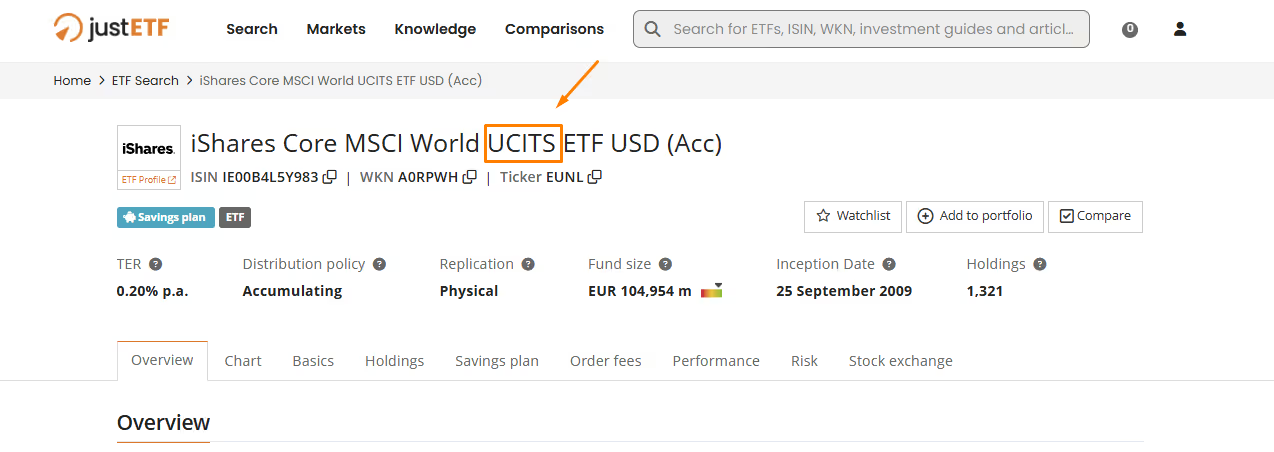

If you go to justetf.com, you will find all UCITS ETFs. How do you identify them? All of them include the word "UCITS" in their name.

For example, if you search for “IWDA”, the ticker of an ETF tracking the MSCI World Index, you will see that its name includes “UCITS” (iShares Core MSCI World UCITS ETF USD (Acc)):

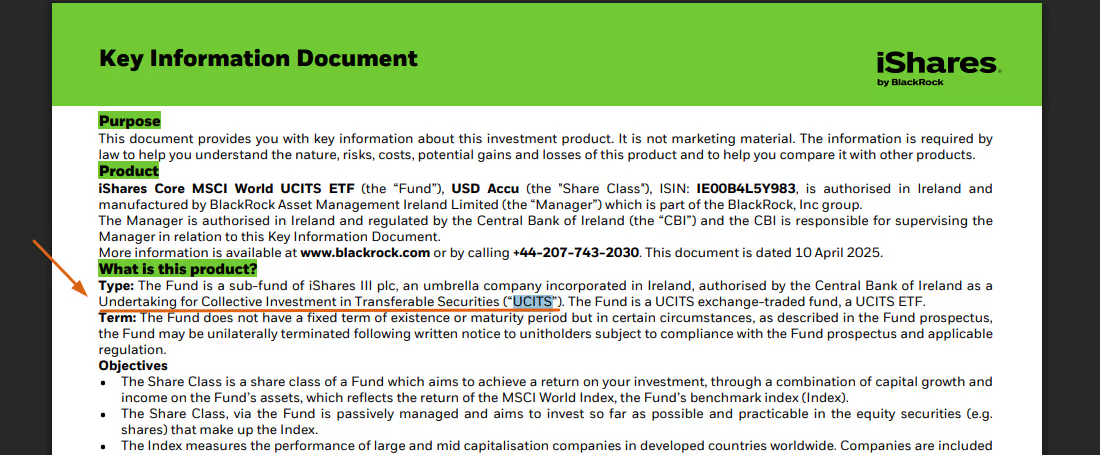

If you want to be 100% sure, just go to its Key Information Document (KID), and you will verify that it is indeed a UCITS ETF:

UCITS vs Non-UCITS (US ETF)

Are UCITS ETFs “safer”?

“Safer” is a dangerous word in investing, UCITS does not remove market risk. You can still lose money.

What UCITS does is standardise a lot of investor protections, notably:

- Diversification rules (avoid extreme concentration).

- Strict rules on leverage and derivatives use.

- An independent depositary with clear liability if assets go missing.

- Standardised cost and risk disclosure, via the KIID/KID and ESMA methodologies (ongoing charges figure, SRRI)

UCITS is therefore best understood as “retail-grade packaging”, a quality stamp that says:

“This fund meets EU standards for diversification, governance, custody, risk management and disclosure to be sold to retail investors.”

It does NOT say:

“This investment cannot go down.”

Why can’t EU retail investors buy many US-domiciled ETFs?

Because of PRIIPs rules.

To sell any US ETF to EU retail clients, it must provide a PRIIPs KID. US ETFs do not produce it, so your EU broker blocks the purchase.

This is why trading platforms like DEGIRO, IBKR Europe, Trading 212, among others, restrict US ETFs.

The European Parliament has explicitly recognised that this effectively means restricted access to US ETFs for ordinary EU retail investors, partly because US issuers would need to adapt to EU-specific performance and cost disclosure rules to create a KID.

Fees: TER vs OCF vs US “expense ratio”

Under UCITS, the old term TER (Total Expense Ratio) was replaced in the KIID by the Ongoing Charges Figure (OCF), which includes management fees, administration, custody, registration, transfer agency, directors’ fees and other operating costs, etc.

It excludes portfolio transaction costs, performance fees, and some extraordinary costs (disclosed separately).

So the OCF of a UCITS ETF tends to be a broad and fairly standardised measure of ongoing costs charged at the fund level.

Many UCITS factsheets still informally say “TER”, but if they’re UCITS-compliant, the number used in the KIID/KID should be calculated by the OCF methodology.

What does this mean for comparing a UCITS ETF with a US ETF?

You can compare the headline % figures, they are all measures of ongoing fund-level costs.

But you should remember:

- UCITS OCF is based on a specific ESMA methodology and usually includes a broad set of operating costs.

- US expense ratios follow SEC rules - they are broadly comparable but not calculated by exactly the same recipe.

So a difference like 0.06% vs 0.07% is probably realistic and meaningful. A difference like 0.06% vs 0.26% deserves deeper inspection:

- Is the UCITS fund more complex (e.g. small-cap, synthetic replication, currency hedging)?

- Is it much smaller (fewer economies of scale)?

- Is it using different counterparties/derivatives that increase costs?

- Is the strategy actually different (different index, sampling, or active overlay)?

For Americans: does it make sense to buy UCITS ETFs?

Usually NO, because:

- US ETFs give Americans better tax treatment

- US ETFs have lower expense ratios

- UCITS funds add unnecessary layers of cost and regulation for Americans

Exception:

Americans living abroad sometimes use UCITS ETFs to avoid PFIC tax rules, but this must be handled with specialist tax advice.

FAQs about UCITS ETFs

Do I have to buy UCITS ETFs as an EU resident?

In practice, yes, if you are a retail investor, and you use a broker or bank regulated in the EU.

Those intermediaries must comply with UCITS/PRIIPs rules and generally only offer UCITS-compliant or KID-compliant ETFs to retail clients.

Is a UCITS ETF always more expensive than a US ETF?

Not always. For example, the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (EEM) has a TER of 0.72%, whereas the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets UCITS ETF (EIMI) has a TER OF 0.18%.

In other cases (especially small-cap, niche or factor strategies), the UCITS versions can be noticeably more expensive, sometimes because: fund size is smaller, replication is more complex, securities lending or hedging is used differently, and there is less competition in that niche in Europe.

Are non-UCITS ETFs “illegal” for EU citizens?

No. The important distinction is:

- Non-UCITS ETFs are not illegal.

- But EU regulation makes it hard or impossible for EU-regulated brokers to sell them to retail clients if there is no PRIIPs KID.

So the problem is “your broker is not allowed to offer it to you”, not “you, as a person, are banned from ever holding it”.

Does UCITS change how my ETF is taxed?

UCITS is about regulation, not taxation. Taxation depends mainly on: the fund’s domicile (Ireland, Luxembourg, US, etc.), and your own tax residence and local tax law.

UCITS funds often use domiciles like Ireland that have favourable double-taxation treaties for withholding tax on dividends, which can be beneficial for many EU investors, but the details are highly country-specific.

Does UCITS guarantee transparency on costs?

UCITS, plus the associated ESMA guidelines, do enforce a standardised way of showing ongoing charges, and PRIIPs adds another layer of standardisation via KIDs.

However, transaction costs, performance fees and some extraordinary costs can still sit outside the OCF. Securities lending revenue and costs are often disclosed in the report, not the OCF.

So transparency is much better than in a world without UCITS/PRIIPs, but “read the prospectus and reports” remains good advice.